This is a work in progress.

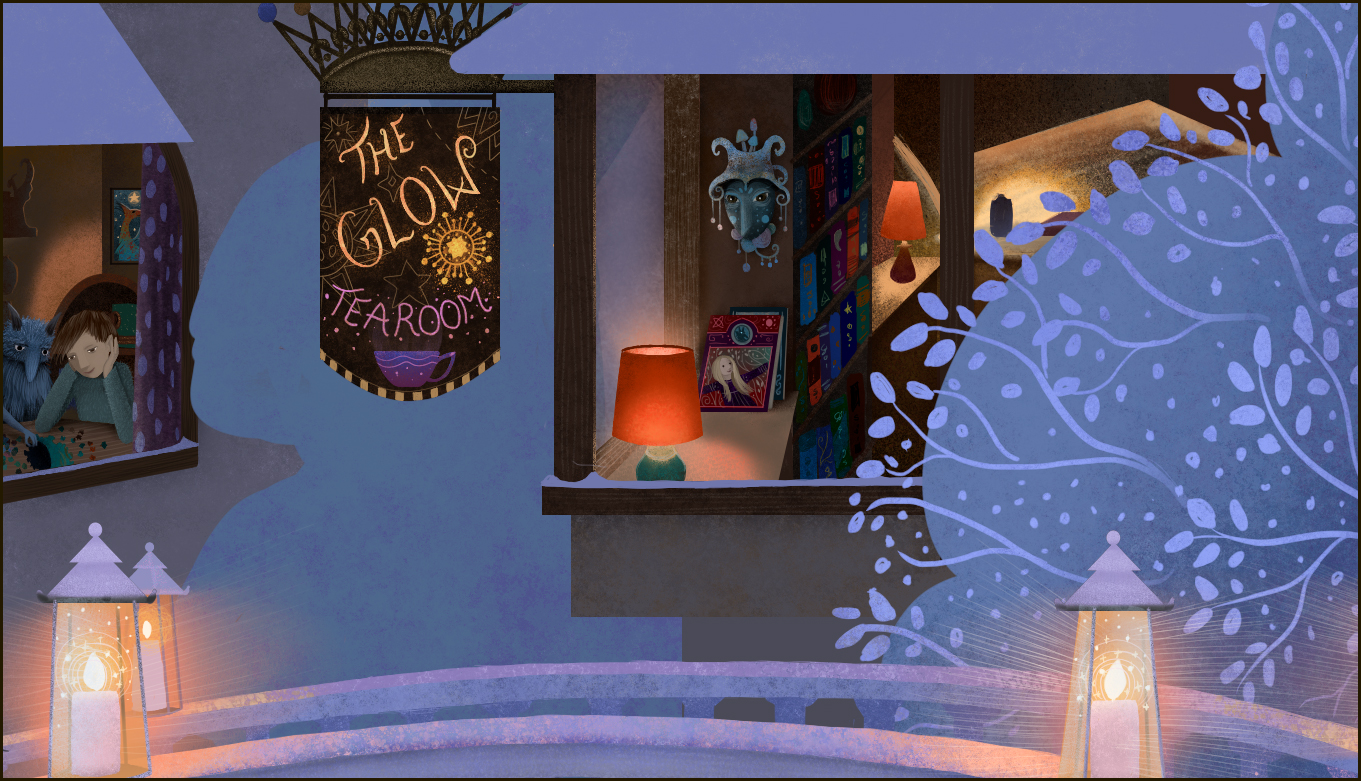

I love spending time in my snowy town in the company of its sweet and gentle inhabitants.This lady in particular is very kind. I also like the boy and his monster. I love painting the interiors you can see through the windows. This is SO MUCH fun!

A proper Christmas card this morning. No wind and clear skies for the rest of the day. But there’s a catch… it’s minus 12.

Play Video

Play Video

Play Video

Play Video

Sometimes when it snows as the evening falls, I think of Sabriel from the Abhorsen trilogy by Garth Nix, the precise moment when Sabriel, searching for her father the Abhorsen (a sort of magus who goes to Deaths’ realm in order to bring back souls or to prevent the dead from entering this world), goes through the gate leading to the Old Kingdom, a land which is forbidden to anyone who is not native. It is a world ruled by magic, the tamed one through the Charter signs but also the dangerous wild magic. Technology doesn’t work there, so Sabriel has to go on skis. I can hear the sound her skis make in the very still snowy forest, her apprehension of being alone in this vast territory where ancient powers rule. But she is not unprepared, she is the Abhorsen’s daughter, an Abhorsen in waiting herself and she carries the magical bells, tools of the trade:

Sometimes when it snows as the evening falls, I think of Sabriel from the Abhorsen trilogy by Garth Nix, the precise moment when Sabriel, searching for her father the Abhorsen (a sort of magus who goes to Deaths’ realm in order to bring back souls or to prevent the dead from entering this world), goes through the gate leading to the Old Kingdom, a land which is forbidden to anyone who is not native. It is a world ruled by magic, the tamed one through the Charter signs but also the dangerous wild magic. Technology doesn’t work there, so Sabriel has to go on skis. I can hear the sound her skis make in the very still snowy forest, her apprehension of being alone in this vast territory where ancient powers rule. But she is not unprepared, she is the Abhorsen’s daughter, an Abhorsen in waiting herself and she carries the magical bells, tools of the trade:“Ranna,” she said aloud, touching the first, the smallest bell. Ranna the sleepbringer, the sweet, low sound that brought silence in its wake.

“Mosrael.” The second bell, a harsh, rowdy bell. Mosrael was the waker, the bell Sabriel should never use, the bell whose sound was a seesaw, throwing the ringer further into Death, as it brought the listener into Life.

“Kibeth.” Kibeth, the walker. A bell of several sounds, a difficult and contrary bell. It could give freedom of movement to one of the Dead, or walk them through the next gate. Many a necromancer had stumbled with Kibeth and walked where they would not.

“Dyrim.” A musical bell, of clear and pretty tone. Dyrim was the voice that the Dead so often lost. But Dyrim could also still a tongue that moved too freely.

“Belgaer.” Another tricksome bell, that sought to ring of its own accord. Belgaer was the thinking bell, the bell most necromancers scorned to use. It could restore independent thought, memory and all the patterns of a living person. Or, slipping in a careless hand, erase them.

“Saraneth.” The deepest, lowest bell. The sound of strength. Saraneth was the binder, the bell that shackled the Dead to the wielder’s will.

And last, the largest bell, the one Sabriel’s cold fingers found colder still, even in the leather case that kept it silent.

“Astarael, the Sorrowful,” whispered Sabriel. Astarael was the banisher, the final bell. Properly rung, it cast everyone who heard it far into Death. Everyone, including the ringer.

This painting is inspired by the second volume in the series, Lirael, and figures the Abhorsen’s house (the dead cannot cross waters).